It’s been a while!

If you’re new, we strongly suggest starting at the beginning, right here.

On December 12, 1926, hired banjo player Bob Tappin was performing “Yes We Have No Bananas” in a ballroom of the Swan Hydro Hotel in Harrogate when a woman dancing the Charleston caught his eye. She was dressed smartly and looked to be having a blast, apparently unaware or unconcerned that she was the subject of a large-scale manhunt that began over a week before, when her abandoned car was found dangling over a ditch near a pond called “The Silent Pool,” where two children were rumored to have drowned mysteriously. The woman was Agatha Christie, the prolific author of popular and occasionally scandalous murder mysteries, having the time of her life—while much of Britain feared she was dead.

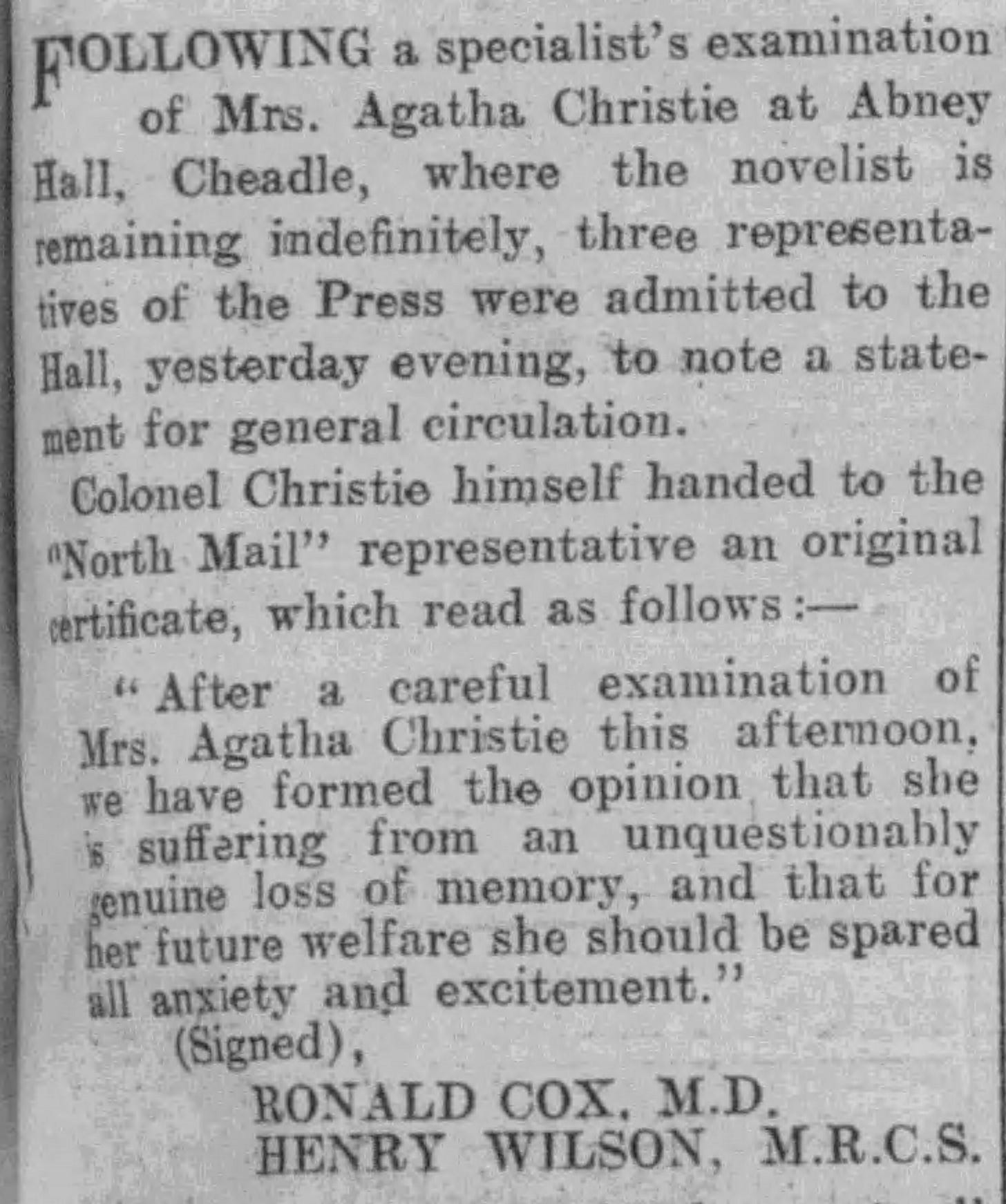

Agatha Christie had last been seen leaving her home, Styles, in Sunningdale on December 3. The discovery of her beloved Morris Cowley roadster led to the massive police and volunteer civilian search along with intense speculation about her disappearance. Her husband, Colonol Sir Archibald Christie, was the subject of much of this scrutiny, and some suspicion, but insisted that Agatha had been happy at home and that he and his wife “had no quarrel.”

This was a lie. The couple had indeed quarreled, most recently about Archie’s stated ambition to leave his wife and marry his mistress, his young secretary and fellow golf enthusiast Nancy Neele. This name is an important detail that to my eye challenges one leading theory that Agatha was in a stress-fueled fugue state at the time of her disappearance, and didn’t know what she was doing. When she checked into the high-end hotel, she said she was visiting from South Africa (perhaps to avoid having to give a local address) and that her name was Teresa Neele. This seems an unlikely coincidence. Because Agatha Christie’s name and face were on the front pages of newspapers distributed at the hotel, there seems to be one of only two possibilities: Agatha truly didn’t know who she was, or didn’t want anyone else to know.

But as with everything connected to this enduring mystery, nothing lines up neatly. If Agatha really was herself, why wasn’t she more discreet in attempting to conceal her identity? Why was she dancing the Charleston at a spa hotel when nearly all of England was searching for her, by air and land? Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who Agatha deeply respected, joined in the hunt – bringing a glove left in the Morris Cowley to a medium, who said, correctly, that the missing author was still alive.

Agatha never gave anything close to a complete account of her disappearance, and skipped right over those weeks in her memoir. In almost every phase of the story there is disagreement and inconsistency, including about who first clocked Agatha. It wasn’t Bob Tappin, but rather a hotel chambermaid, Rosie Asher, who initially suspected Agatha Christie might be staying at the hotel. Agatha had a taste for high fashion that she did not pause during her vanishing. Rosie had noticed the guest’s buckled shoes and a zipper on her purse, the latter rarely seen elsewhere besides magazines at the time, Jared Cade wrote in Agatha Christie and the Eleven Missing Days, a well-sourced account that posits Agatha’s disapperance was driven by the bitter betrayal of her husband, not a psychogenic trance (the thesis of Andrew Norman’s more recent book.) Rosie Asher didn’t go to the police, later saying the trouble wasn’t worth her job, so Tappin got the credit for ‘finding’ Christie. It remains unclear if he ever collected the reward.

Agatha Christie had no shortage of existential grievances, and was given to crying jags and at least one nervous breakdown in the months preceding her disappearance, when she was grieving the loss of her mother to bronchitis. Colonel Christie, who was by all accounts a right cad, had no patience for his wife’s grief or her mother’s previous illness, and his emotional abandoment long preceded his decision to leave her for good. Her mother Clara had warned her not to marry Archie, but Agatha was smitten, and remained so even as the marriage became irrevocably broken. They had a daughter, Rosalie, who was closer to her father than her mother —to Agatha’s chagrin— and was left in the care of hired help when Agatha drove off on December 3, 1926. Rosalie was 7 at the time.

Before and after Agatha was found, her husband had an interest in controlling the narrative; and by all indications she let him. This is curious. Perhaps Agatha preferred the nervous breakdown explanation Archie offered, and enjoyed a rare event of solidarity —presenting a story that both knew to be false— with the man who had cast her away and cruelly dismissed her pleas for reconciliation. Or maybe she chose not to suffer further humiliation by exposing her husband’s affair; something Archie Christie was quite keen on keeping a secret himself, so as not to embroil his future wife in a scandal. One wonders if Agatha enjoyed watching him squirm. As Cade wrote, Agatha —who insisted on changing into an evening gown when Archie came to fetch her at the hotel, press cameras waiting— seemed intent on making sure her husband “knew what he was missing.”

When Steven Kubacki reappeared after going missing during a cross-country skiing trip 14 months earlier, he made a point to tell reporters that he had “no trouble with girls.” His only trouble, apparently, was having more than one of them. (All overseas; it remains unclear how Kubacki kept up these romances.) He insisted that he was in a perfectly healthy state of mind, despite suffering from apparent amnesia, and would not be seeking any psychiatric help.

Today, Kubacki is a Seattle-based psychotherapist, and he has ignored my requests to speak with him for nearly three years. As I wrote before, there is good reason to believe Kubacki was not in a so-called psychogenic trance —a stress-induced dissociative state marked by memory lapse— when he was missing between February 1978 and May 1979. What I don’t know is whether Kubacki at any time believed that he had been. It seems clear that with his insiders, he changed his story over time, but I don’t know why, or exactly how.

I’ve been conflicted about the intrusiveness of reporting on a newsworthy event involving someone who, unlike Agatha Christie, is far from a public figure. Naively, when I first came across Kubacki’s story, I believed he would be happy to talk about it; maybe it’s just that no one had asked him about in in four decades. I was very wrong. And I can now think of more scenarios that would make someone in his position reluctant to talk, rather than eager to.

Many of the people I have contacted or tried to contact have been unreachable or flatly refused to speak to me (including Kubacki’s ex-wife). The Dean of Students at Hope College at the time of Kubacki’s disappearance, who appeared to believe it was some kind of stunt, died before I began researching this project. I feel confident that Kubacki’s roommate at the time knows something, but he hasn’t responded to multiple requests for an interview. And sometimes I have to ask myself: Why would he? As a journalist, I’m still occassionally amazed when people volunteer information under no obligation, with no motive other than getting the truth out. There are often more downsides than upsides. But I supppose that depends on what the truth is.

Besides the roommate and the Dean of Students, I’ve been particularly eager to speak to the people who first encountered Kubacki when he ‘woke up’ in a grassy field in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, on May 5, 1979, after he had long been feared dead. As the story goes, Kubacki remembered some of himself and hitchicked to his Aunt June’s home in Great Barrington. The theology student who picked him up later told the Associated Press that Kubacki gave him a different name than Steven. But this person has since been involved in a rather scandalous situation of his own, and did not return any of my inquiries.

After several unsuccessful attempts to reach Kubacki’s aunt by phone, I knocked on her door this fall during a visit to Great Barrington. Dressed in a Saturday morning housecoat, she closed the door in my face, not impolitely. What I saw in her eyes was not anger, but fear. Was it me she was afraid of, or something else?

This chapter closes, for now, with the defeated journalist cliche: I’m left with more questions than answers. And not just about what Steven Kubacki was doing for those untraceable 14 months. What do we have a right to know, and when do we have a right to know it? Is it resources spent, people hurt, the possibility of a government-concealed alien abduction? I’m disappointed with how little I have been able to determine. But I won’t stop asking Kubacki to let me tell his story.